Five times politics overshadowed sports at the Olympics

Are you interested in taking action for issues that are important to you? Check out our Civic Engagement page.

Written by Eric Revell, Countable News

The Olympics aspire to bring out the best in humanity through a celebration of athletic achievement and international cooperation, based on the belief that a “peaceful and better world” can be built through respectful competition. But as history has shown, when so many countries get together in one place things can get pretty damn political.

The U.S. has been sending athletes to the Olympics since 1896, and on several occasions, global and domestic politics overshadowed the sporting side of the Games. This year’s Winter Olympics hosted by the People’s Republic of China in Beijing will be another such occasion. The U.S., Great Britain, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium, Lithuania, Estonia, Kosovo, and India are undertaking a diplomatic boycott of the Games in which athletes will participate but no dignitaries associated with those governments will attend due to the human rights abuses of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

The boycotts have been prompted China’s ongoing genocide and crimes against humanity targeting Uyghur Muslims and other ethnic minorities in Xinjiang, where a million Uyghurs have been detained in concentration and work camps. There they have been subjected to forced labor, systemic rape, compulsory abortions, sterilization, in addition to undergoing indoctrination with communist propaganda. Outside the camps, Uyghurs are subject to mass surveillance and restriction of their movements.

Aside from China’s treatment of the Uyghurs, a number of other issues between the PRC and the West are simmering while athletes are competing. The CCP quashed democracy in Hong Kong; is attempting to coerce the nation of Taiwan, and has been belligerent toward India and countries in the South China Sea. China also continues its suppression of a free press and its pervasive surveillance has prompted warnings that athletes should use “burner” phones and rental computers and refrain from speaking out against the CCP while they’re in the country. Further, the Games are being held amid the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, which originated in Wuhan, China, where the CCP has obstructed international efforts to investigate the origin of the virus.

The CCP offered a rebuttal to the boycotts in the opening ceremonies of the Beijing Winter Olympics. It placed athletes from Taiwan ― which competes in the Olympics under the name “Chinese Taipei” because the PRC has sought to prevent other countries from recognizing an independent Taiwan ― in line next to the Hong Kong delegation, with a pro-CCP commentator taking pains to emphasize the naming distinction. The CCP also had a commander of the People’s Liberation Army forces who fought the Indian military during a border skirmish in 2020 serve as a torchbearer; while a Uyghur athlete was chosen to co-light the Olympic flame.

With the Olympics now underway in Beijing, we’ve recapped five other times when politics trumped sports at the Olympics.

1936 Berlin Olympics

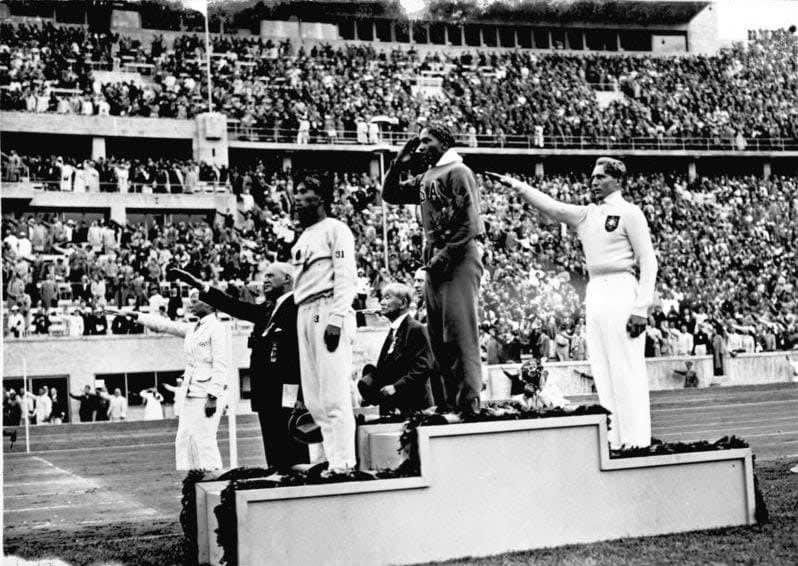

Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Germany hosted the 1936 Olympics, viewing the Games as an opportunity to demonstrate to the world that the country had rebuilt itself into a major European power following World War I. Grounded in the Nazi’s ideology of racial superiority, Hitler’s regime had already consolidated its power and put in place discriminatory anti-Jewish policies in advance of the Games, leading to substantial debate about whether the U.S. should boycott the Olympics in protest.

Those calls went unheeded, which allowed track and field athlete Jesse Owens, an African-American, to go out and win four gold medals in the 100m and 200m sprints, long jump, and 4x100m relay in Hitler’s Germany. The silver medals in the 100m and 200m sprints also went to two of Owens’ black teammates: he edged Ralph Metcalfe (who later served four terms in Congress) in the 100m by one-tenth of a second; and Mack Robinson, the older brother of baseball player Jackie Robinson, in the 200m by 0.4 seconds.

The controversy surrounding the 1936 games wasn’t confined to the decision to send a U.S. team to Berlin. Two Jewish-American sprinters — Marty Glickman and Sam Stoller — were pulled from the 4x100m relay team on the day of the race in favor of Owens and Metcalfe, and accused the U.S. of pulling them in order to avoid embarrassing Hitler and his regime. While no proof ever emerged that anti-Semitism drove the decision, in 1998 the U.S. Olympic Committee awarded plaques “in lieu of the gold medals they didn’t win” to Glickman and posthumously to Stoller.

1968 Mexico City Olympics

The 1968 Mexico City Games featured a number of outstanding performances by American athletes between Bob Beamon shattering the world long jump record by 21 inches, Dick Fosbury winning gold while revolutionizing the high jump with the Fosbury Flop, and Jim Himes becoming the first sprinter to break the 10-second barrier. They also featured perhaps the most overtly political protest in modern times amid what was already a politically charged year due to the Vietnam War intensifying and the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert F. Kennedy.

The stage was set for the protest following the 200m finals, where African-Americans Tommie Smith and John Carlos won the gold and bronze medals, respectively. Smith had set a world record in the race. During the medal ceremony, the two men were joined by Australian silver medallist Peter Norman, and all three wore badges from the Olympic Project on Human Rights to protest racial discrimination. (Norman, a white man, was a critic of an Australian policy restricting immigration to his country by non-whites.)

But it wasn’t the human rights badge that made the protest so controversial. Smith and Carlos planned to receive their medals shoeless while wearing black socks to represent the poverty faced by many blacks in America. Smith wore a scarf to represent black pride, while Carlos opened his collar to show solidarity with the working class and a necklace representing blacks killed because of their race. They’d planned to both wear black gloves to the ceremony but only brought one pair, so at Norman’s suggestion, they each wore one glove.

As “The Star-Spangled Banner” played after they were awarded their medals, Smith and Carlos each bowed their heads and raised a fist in a black power salute. While they were booed by the crowd when they left the podium, the men had made their mark; their protest soon became front-page news around the world and the moment was immortalized by this iconic photo:

1972 Munich Olympics

The 1972 Summer Olympics are remembered less for what happened during any athletic competition than for the horrific intrusion of terrorism into the Games in what’s known as the “Munich Massacre.” A Palestinian terrorist group known as Black September broke into facilities housing Israeli athletes with an eye toward taking hostages in order to secure the release of 234 prisoners in Israel and two in Germany.

The terrorists killed an Israeli athlete and a coach during the initial break-in and managed to take nine hostages. One Israeli athlete, a racewalker named Shaul Ladany, was awakened by the screams of one of his teammates and escaped the building, reaching the nearby American dormitory and alerting U.S. track coach Bill Bowerman to the situation. While Ladany notified German police, Bowerman ― a World War II veteran of the 10th Mountain Division ― called the American Consulate in Munich to get a detail of Marines to come to the Olympic Village to protect two Jewish-American athletes who were staying at the Village: swimmer Mark Spitz, who won seven gold medals in Munich, and javelin thrower Bill Schmidt.

Events at the Olympics were postponed for more than a day to deal with the hostage crisis, which allowed President Richard Nixon time to discuss the situation with his cabinet, all of which was picked up by Nixon’s soon-to-be infamous office recording system. After speaking with National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger, Secretary of State William Rogers, and Kissinger’s adviser Alexander Haig, Nixon decided that the U.S. should press the United Nations to counteract international terrorism through rules about harboring militants.

Following negotiations with the terrorist group, the hostage situation ended tragically when a rescue attempt carried out by German police went awry and a police officer and all nine hostages were killed.

1980 Moscow Olympics

The Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan in December 1979 cast a shadow of darkness over the upcoming Summer Olympics, which were slated to be held in Moscow. In early 1980, President Jimmy Carter threatened that the U.S. would boycott the Games unless the Soviets withdrew from Afghanistan.

A boycott of the Olympics wasn’t unprecedented: 30 African countries boycotted the 1976 Montreal Games after New Zealand was allowed to compete despite sending its rugby team to apartheid South Africa for a match. Taiwan pulled out of those Games as well after China lobbied Canada into denying them the right to compete. Still, detractors argued that a boycott would be seen as a symbolic ― rather than strategic ― gesture and wouldn’t lead to a Soviet withdrawal.

But ultimately, the U.S. went forward with the boycott, along with more than 60 other countries. Some of them allowed athletes to decide individually whether they’d compete, including the United Kingdom, France, and Australia. But others such as Japan and West Germany joined the U.S. in a full boycott of the Games. Many of those athletes competed instead at the “Liberty Bell Classic” which was held that year in Philadelphia and funded through $10 million from Congress.

1984 Los Angeles Olympics

The adage that “what goes around comes around” rang true following the U.S.-led boycott of the Moscow Games as the Soviet Union, the communist Eastern Bloc, and some other socialist countries decided to boycott the Los Angeles Olympics four years later.

Just a few months before the opening ceremonies were to begin, the Soviets announced that they wouldn’t compete due to security concerns, in addition to “chauvinistic sentiments and an anti-Soviet hysteria being whipped up in the United States.” The countries also complained that the Los Angeles Olympics Committee had allowed the Games to be commercialized by big business, and in so doing they were “perverting the Olympic ideals.” Iran also boycotted over America’s support for Israel, “interference in the Middle East,” and interventions in Latin America.

Just prior to the boycott announcements, relations between the Soviet Union and the U.S. reached a low point after a South Korean commercial airliner was shot down by the Soviet military, killing all 269 people aboard. In spite of public outrage and attempts to ban the Soviets from the Games, President Ronald Reagan and his administration continued to work to accommodate the Soviet Union’s requests to ensure their participation and vowed not to discriminate against them.

Ultimately, those attempts were unsuccessful and the Soviet boycott spawned a similar spin-off to the 1980 Liberty Bell Classic, as the “Friendship Games” were held between the Soviet Union, North Korea, and six other Eastern Bloc nations. While President Reagan believed a fear of Soviet athletes defecting to the U.S. may have played a role in the boycott, Howard Tyner of the Chicago Tribune summed up the prevailing rationale:

“Deep down, it was undoubtedly the hurt and embarrassment of 1980 that lies behind the stunning Soviet decision Tuesday to pass up this year’s Summer Olympic Games in Los Angeles.”

(Main Photo Credit: Bundesarhiv, Bild via Wikimedia / Creative Commons | 1968 Black Power Salute: Angelo Cozzi (Mondadori Publishers) via Wikimedia / Public Domain)